August 1, 2013

Given the Choice

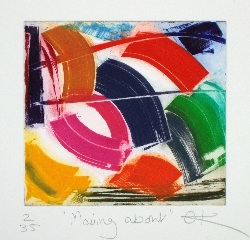

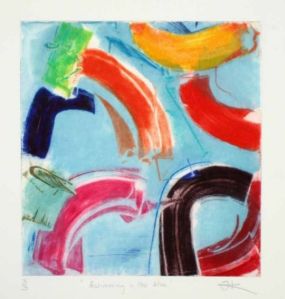

I am delighted to announce that my new novel, Given the Choice, will be published by independent publisher Cillian Press next month. Set in the contemporary art and music worlds, the cover features original artwork by Olivia Krimpas.

I am delighted to announce that my new novel, Given the Choice, will be published by independent publisher Cillian Press next month. Set in the contemporary art and music worlds, the cover features original artwork by Olivia Krimpas.

Next month, I’ll be blogging with more details about the novel, but for now here is a taster.

In this passage, French painter Jean-Claude is in New York for the opening of his show. He has come to Hoboken, and is looking out across the Hudson River at the night skyline.

“At this distance, the city seemed a fantasy creation, an enchantment conjured by a magician from the sea. Jean-Claude lit his cigarette and walked along the esplanade, noting the extraordinary crenellation of illuminated buildings, the glittering jetties that stuck out from the shore like afterthoughts. The esplanade led him past a clump of shadowy trees and round a slight bend. The city’s brilliance, he saw, derived from millions of individual lights, from the chequerboards of lit up windows that formed the facade of building after building. Most were interior lights, but there were also bands of colour: a glowing orange top floor, a tower in a tracery of red neon, a glass-front that sparkled an ethereal green-blue. Light hurled itself upwards into the sky, leaked onto the surface of the water where it settled in channels that appeared solid enough to walk on.”

In this passage, Marion, who runs an agency for artists, listens to a young Estonian pianist play an excerpt from one of the many pieces composer Olivier Messiaen wrote based on birdsong.

“Peeter placed his hands over the keys. Suddenly the piano was alive. Marion settled back in her chair and closed her eyes. She did not know what she was listening to but within moments she was transported out of her surroundings into a dense jungle of sound. The piano was no longer a music-making machine but the source of a magical power. She could hear the swooping calls of birds as they darted through treetops or skimmed and dived in a free expanse of air. The bare walls of the practice room had metamorphosed into an enchanted forest, teeming with flashes of brilliant plumage and abrupt, raucous caws. As she opened her eyes she was reminded of the monastery of San Marco in Florence, its plain white cells transfigured by Fra Angelico’s art. She thought of the ritual of Peeter’s daily practice. The long hours he spent at the keyboard required the same devotion the monks expended in prayer. When Peeter finally stopped playing she felt as if he had taken her to a world beyond herself, where she had glimpsed something extraordinary. It was a feeling she sometimes had when she looked at art.”

For more details, please check back on 1st September

October 24, 2010

Turning a novel into a play

Sebastian Faulks once remarked that transposing a novel to another medium is like trying to turn a painting into sculpture.

It’s an image I’ve been thinking about this summer as I’ve watched Vanessa and Virginia transform into a stage play.

What first struck me on reading Elizabeth Wright’s script was the drastic scissoring away of words. Anything not absolutely essential to moving the story forward had been ruthlessly cut. Probably I should have expected this: a play script is after all considerably shorter than a novel.

What I could not have anticipated, though, was the economy with which words were used in rehearsal. I vividly remember director Emma Gersch encouraging the actors to play games together as they searched for a way to perform the childhood scenes. They were asked to chase and mimic each other, to compete against each other, to explore the walls and furniture with their hands – but not to speak. Eventually they were allowed to include one line from the script in their games.

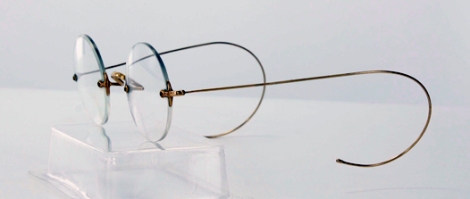

This different emphasis – on physical and emotional exploration rather than words – continued through the rehearsal process. One afternoon designer Kate Unwin returned from a shopping expedition with a pair of round-framed spectacles she had found in a local charity shop. Immediately, Sarah Fullager (who plays Virginia) began working with the spectacles in an attempt to locate a point of empathy with the older Woolf. Watching the alterations the spectacles occasioned in her demeanour was riveting.

All this makes me wonder if Sebastian Faulks’ metaphor is the right one. What defines sculpture as a medium is its stillness: a viewer must move round it to see all its angles. A play, on the other hand, is anything but still. As I learned from watching the rehearsals for Vanessa and Virginia, in the theatre everything – from the actors’ bodies to lighting – is there to bring the characters and their stories to life.

I’m trying to think of a better analogy….

October 16, 2010

My perfect writing day

There’s a fascinating discussion going on at She Writes about what constitutes the perfect writing day.

Here’s mine.

I wake up having had enough sleep. This is important – if I’ve had one of those nights where it feels as if the world’s traffic has been using my brain as a concourse I can forget about writing.

The day will be with one with nothing else in it. The ‘to do’ list I revise each evening and leave for myself in the centre of my desk will have one word on it: writing.

Tea (strong, with a little milk), a bowl of high-energy cereal, then a brief venture outside. I walk the few steps to the garden gate and peer over it. Two giant Ash trees grow opposite and I watch them for a moment, thinking how Virginia Woolf described taking ideas to her writing hut each morning like a delicately balanced basket of eggs.

If whatever I am writing is already well advanced I start as soon as I get to my desk. If it isn’t – if I am still feeling my way in to the characters and their story – then the process of beginning takes longer. Sometimes all I achieve are notes.

I force myself to exercise at the end of the morning: yoga, aerobics, if the weather is good a walk or run. My reward is lunch which I eat listening to the words in my head, outside if I can.

Unlike most writers I know, I always do my best work in the afternoons, beginning about 2 and working through to 4 or sometimes 5. After this, no matter how well the writing is going, I come to a natural stop. I look forward to my son returning from school, to switching on email and letting the world flood in.

Oh, and my perfect writing day ends with the knowledge that tomorrow will be exactly the same.

October 9, 2010

Displacement before writing

Why is it so difficult to start a piece of writing? This week I cleared space to begin working on a new novel but for some reason I have managed to fritter away the time, persuading myself that I really should send that reference/keep on top of my inbox/clean out the fridge/take that picture I’ve had since Christmas to the framer.

It isn’t fear of the blank page that’s stopping me. I have my characters, the setting, I even know some of the things that are going to happen in my story. I am eager to fill in the gaps. But for some reason I keep putting off the start.

Writing a novel is often compared to a journey, full of lows as well as highs, and some of my prevarication is perhaps analogous to what I imagine a long-distance swimmer might feel before diving in. Part of me longs to be in the water again, while another part is reluctant to leave dry land. It’s a question of preparedness too – to write you have to accept that for months to come you won’t be available to attend to all life’s details and that some things, frankly, will slip by the way. At least some of the postponement is practical. References do after all have to be sent, fridges cleaned.

I’ve just looked up the word displacement in the dictionary. One of its meanings is ‘the transfer of emotion to a less threatening source’. This is helpful. There is a fear of failure in delaying writing. While my new novel exists only in my head, it is possible it will convey more exactly than my last one that shadowy but compelling vision I can see bobbing somewhere far ahead of me.

And towards which I know I must swim.

To share your displacement stories, please leave a comment

January 20, 2010

Writing with the door closed, editing with it open

After a talk to the Arts Society at Newnham College in Cambridge last night I had an interesting discussion about the differences between literary criticism and creative writing. The talk was to launch a new journal Women and the Arts, celebrating Virginia Woolf’s lecture to the Society in 1928. Woolf later reworked her lecture as her seminal essay A Room of One’s Own.

After a talk to the Arts Society at Newnham College in Cambridge last night I had an interesting discussion about the differences between literary criticism and creative writing. The talk was to launch a new journal Women and the Arts, celebrating Virginia Woolf’s lecture to the Society in 1928. Woolf later reworked her lecture as her seminal essay A Room of One’s Own.

Woolf was constantly in my thoughts as I spoke, not only because I was talking about my fictional account of her life in Vanessa and Virginia, but also because so much of what she said in 1928 about the necessary conditions for exploration and creation remains true today. We still need space (‘a room of our own’) where we can work without interruption; we still need money so we have time to sit in that space.

In her lecture, Woolf was talking partly about women’s writing (which in 1928 was still markedly absent from the literary mainstream despite notable exceptions), but also about all manner of intellectual and inventive enquiry as encapsulated by her two imaginary female scientists, Chloe and Olivia.

But the discussion after my talk was about writing, and specifically about how as critics we learn to focus on a text’s details so our understanding of the way a particular passage or sentence is crafted becomes highly sensitised. This can make it paradoxically harder for us to write creatively since we scrutinize every phrase we put down – and stumble on its flaws. How, a young writer asked me, can we turn off that critical eye so we can launch into the mess and flow of original production?

This is a crucial question and one that isn’t confined to literary scholars. Reading sharpens our appreciation of what words do and this can impede our efforts to write. We all know the pattern. We stall before we’ve decently begun because some negative, querulous voice forces us to revise what we’ve just written – and then revise it again. We get up from a hard-earned session in that ‘room of our own’ because we persuade ourselves we’re too tired, or too preoccupied, or too uninspired to write today.

Woolf has a good answer to this conundrum. She has an image of herself with a devil-angel on her shoulder, detonating her confidence with doubts and contrary thoughts. In Woolf’s case the source of the devil-angel is the Victorian ideal of perfect womanhood – but though that particular goddess no longer stalks us, others have replaced her.

Woolf’s solution is radical. She argues that we must take the point of our metaphorical pens and stab these devil-angels before they destroy any chance we have of writing ourselves.

I agree: we have to do whatever is necessary to quell these disabling voices. We have to build into that ‘room of our own’ permission to write without censorship. We have to create a space where we can experiment, explore, set off into the unknown: somewhere we can make mistakes. Otherwise we will never reach that alchemical point where writing begins to transport us, suggest possibilities we have not thought of, expand the range of what we imagined possible.

This is not the whole story. Whatever writing we produce during our journey has to be reworked. There will be superfluity, confusion and error mixed in to our work, which we will need to eliminate before it sets. We must review what we’ve written and decide how we will communicate it to others.

Which is where that critical eye comes in, trained up by our years of reading. At this point in the process it’s an aid, not a curb. The editing process is a different operation to that early one of exploring and experimenting and calls for a different mindset.

Or perhaps it just requires us to make an adjustment to our room. Stephen King insists we should write with the door of our writing room closed in order to give ourselves privacy and the freedom to embark. He suggests we should open that door when we edit, considering our potential audience as we draw on those finely tuned critical skills. I think this is helpful. At the beginning of any creative endeavour there has to be a ‘closed door’ period where we can immerse ourselves fully, give ourselves permission to experiment and dare. We can then follow this with an ‘open door’ period where we review what we’ve done – before sending our work out through that door into the world.

September 30, 2009

Weaving

Earlier this month I visited the Gobelins in Paris, where tapestries and carpets are still made by hand using techniques that have hardly changed over centuries. After the history-for-tourists preamble by our guide we were taken on a tour of the workshops. There was something mesmeric about the row of weavers working with only the simplest of tools: a shuttle to pass the thread back and forth, a comb to press the threads flat, a pair of scissors. One of their more surprising tools was a mirror. The tapestries are woven back to front and the mirrors are inserted under the frame so the weaver can see the image they are creating.

Another surprise was the contemporary design of the tapestries and carpets. The Gobelins do not replicate historical artefacts but produce new work based on pictures and photographs by contemporary artists. The resultant pieces are extraordinary: richly textured, they arrest the eye. Some use hundreds of colours. I saw one weaver working on a detail using perhaps a dozen different shades of purple – every possible variation from aubergine to plum. Nothing made at the Gobelins is for sale. Once the tapestries and carpets are finished they are taken to a central store, where they wait to be assigned to a public building.

Watching the weavers clock-off at 4.30 – they weave in natural light if at all possible – made me think about the rhythm of their work. Our guide had told us that in the case of complex designs a skilled weaver might only produce a few centimetres a day – a statistic I find profoundly reassuring when I compare it to my own efforts to inch my current novel forwards. Perhaps if – like the weavers – I keep weaving away at my words, the moment will come when I’ll turn the whole thing over and a marvellous picture will emerge.

September 19, 2009

Can you teach creative writing?

There’s an interesting debate going on in British universities at the moment about the teaching of creative writing. Some argue it can’t be taught – that the best writing derives from a slow process of trial and error conducted alone at one’s desk. Others point out it involves a good deal of craft and insist that just as a painter learns perspective – or a composer scoring for different instruments – so a poet must study metre and a novelist plot.

There is disagreement even among those in favour as to the form such teaching should take. Broadly speaking, the dispute falls into two camps: those who advocate skills-based classes (such as scrutinizing different plot-lines) versus those who champion the workshop (where participants take it in turns to read their work aloud and are given feedback by the group). Both clearly bring benefits. Skills-based sessions offer insight into the technical aspects of writing and often help prepare the writer for the harsh realities of the marketplace. Workshops encourage critical self-appraisal through a tough kind of love.

There is disagreement even among those in favour as to the form such teaching should take. Broadly speaking, the dispute falls into two camps: those who advocate skills-based classes (such as scrutinizing different plot-lines) versus those who champion the workshop (where participants take it in turns to read their work aloud and are given feedback by the group). Both clearly bring benefits. Skills-based sessions offer insight into the technical aspects of writing and often help prepare the writer for the harsh realities of the marketplace. Workshops encourage critical self-appraisal through a tough kind of love.

Each model has detractors. Workshopping (now a verb) can damage as well as build confidence, and can mean a piece of writing is dissected by others before it has acquired its own identity. At its worst, technical courses produce formulaic writing which leaves most industry professionals running for the cover of their slush-piles.

So far, most UK university undergraduate and masters programmes have privileged the workshop over skills-based classes, supplemented with plenty of individual tuition from published writers. Those – like the recent masters at Napier (which foregrounds technique and specifically orients its students towards genres of writing) – remain rare.

But what about the newest and most controversial university course in creative writing: the Ph D? This has taken a while to establish itself in the face of fierce opposition from those who contend creative writing doesn’t belong in the academy at all. And as with undergraduate and masters programmes, even those institutions who now offer the degree have conflicting views as to how it should be assessed. Some require a finished piece of writing – a whole novel, a full collection of poems – reasoning that it’s impossible to judge part of a work. Others propound the Ph. D. has an obligation to include critical analysis, and consequently insist on a sample piece of creative work together with a commentary. The critical component can be as little as 10%, or – as in the case of the University St Andrews where I teach – as high as 50%.

Few of today’s literary giants began with a qualification in creative writing, though there are plenty of stories of writers enrolling for degrees and writing instead (Ian Rankin, for one, has famously described how he used his Ph. D. funding to kick-start his career as a novelist). So is the debate about the precise form creative writing courses should take beside the point? Maybe what’s important has less to do with acquiring technique or gaining feedback from others – and more with giving participants permission to carve out time to write.

May 30, 2009

Juliet Mitchell

I first read Juliet Mitchell in the early 1980s alongside other feminist writers such as Germaine Greer, Kate Millett and Alice Walker. I can still recall the growing sense of entitlement their work gave me: to choose what kind of relationships I wanted to be involved in, what work I wanted to do.

I first read Juliet Mitchell in the early 1980s alongside other feminist writers such as Germaine Greer, Kate Millett and Alice Walker. I can still recall the growing sense of entitlement their work gave me: to choose what kind of relationships I wanted to be involved in, what work I wanted to do.

Earlier this month I attended a one-day symposium in Cambridge to mark Juliet’s retirement from academic life. The morning began with a film clip of Juliet from the 1970s, arguing with passionate earnestness for some of the principles we take for granted today (the absurdity of women agreeing to ‘obey’ their husbands in marriage, for example). Juliet’s more recent work has been on siblings – work I drew on for the writing of Vanessa and Virginia. For Juliet, our failure to navigate the frequently fraught relationships we have with our siblings affects the way we live as adults. She suggests it is a primary ingredient in discrimination, violence and war.

At the end of the day, Juliet responded to the different commentaries people had given on her work. Several of the things she said have stuck in my mind. A reminder of our fragility, and how the past continues to play itself out in our lives. As Juliet put it, ‘traumas continue to ghost, double, return in unpredictable but inevitable ways’. She quoted the axioms we’ve all heard: how disaster often strikes twice, or how we make the same mistake three times. All this left me thinking: how far do we co-create what happens in our lives, even apparently gratuitous events like accidents or falling ill?

A profound thank you, Juliet, for setting me on my path all those years ago, and for continuing to challenge my orientation today.

October 18, 2008

Reviews and reactions

‘In short, disconnected scenes of exquisite description and nuanced emotion, Susan Sellers invites us to assemble the pieces into a picture not only of the Bloomsbury circle, but of the exigencies of creative work as outlet, devotion, and anchor. A fascinating, compelling novel written with authority and tenderness.’

Susan Vreeland, author of Girl in Hyacinth Blue.

‘Reading Vanessa and Virginia is like swimming across the seabed of the minds of sisters Woolf and Bell – everywhere there are fragments of paintings and scenes from novels and lyrical phrases scattered like sunken treasure. It is a novel both exquisite and haunting. A triumph of the imagination.’

Rebecca Stott, author of Ghostwalk.

‘Deftly, apparently effortlessly, Susan Sellers’s novel of love, art, and sexual jealousy gives us convincing and intimate access to the relationship between two remarkable sisters. At once pellucid and sophisticated, Vanessa and Virginia is quite simply a pleasure to read.’

Robert Crawford, author of Full Volume.

‘profoundly insightful… Vanessa emerges as such a vibrant, brave, complex and living woman…. the love/hate relationship between the two sisters, the strange exchange of places between them, the tenacity of their attachment to parents, brother, the passion of the affairs are convey so vividly. An extraordinary coup.’

Nicole Ward Jouve, author of Colette.

‘Vanessa and Virginia is a beautifully written novel. Vanessa’s story is formed, as one might expect of an artist-narrator, from painterly prose… Sellers achieves a believable psychological reality in the figure of Vanessa, who, as narrator, leads the reader through a series of interconnected pictures, much as the viewer wanders the corridors of an art gallery pausing from canvas to canvas…Vanessa’s memory moves across years and through moments with sensitivity and grace, so that the reader is seamlessly transported from place to place, event to event, feeling to feeling. It is a difficult structure, but Sellers successfully achieves unity in its execution…

As a Woolf scholar [Sellers] is meticulous in her attention to facts and details, but through Vanessa’s voice she reminds the reader that ‘art is not life’… Sellers does not succumb to sycophancy as both sisters’ foibles and flaws lie side by side with their genius. Her even-handed approach to their strengths and weaknesses creates a believable reality which the reader (Bloomsbury expert or not) can fully appreciate. Sellers’ command of her material, her ability to create Post-impressionist pictures with words and her mastery of the difficult pastiche form, means that her work stands as a literary success in its own right, neither overpowered nor overshadowed by the artistic achievements of her subjects.’

Elizabeth Wright, in The Virginia Woolf Bulletin.

‘I was hugely impressed by this accomplished first novel. It traces the complex artistic and emotional interweaving of the lives of sisters Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf. The story, told from Vanessa’s perspective, is passionate, intimate and entirely lacking pretension. The ending comes, as we know it must, with Virginia’s suicide. And yet Susan Sellers has managed to deliver the expected and for it to still shock and upset us. This is a truly great book and I hope to see more from this talented writer.’

Matthew Perren, I-On Edinburgh.

‘Vanessa and Virginia is fictional, but based on real people and events – the childhood of Vanessa and Virginia Stephen, later to be artist Vanessa Bell and novelist Virginia Woolf, and their subsequent lives up to the death of Virginia. It is from the perspective of Vanessa, and addressed to Virginia (though without expecting response). Sellers’ style is not an imitation of Woolf’s, but it has deep similarities – the same beautiful lyricism, use of abstract images, delving into human emotions with an intelligence and compassion which never stumbles into the saccharine… I was wrapped in the beauty of the language and never wanted to leave. [Sellers has written] a beautiful novel which does justice to Bell’s perspective as a very talented painter, overshadowed by a very talented novelist sister, in an unusual group and unusual time. I don’t know where Sellers can go after this, but I look forward to finding out.’

Simon Thomas. For the rest of this review, click on: ‘stuck-in-a-book’ review

‘…not only have I learned something about Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf, but it is one of those novels that has something profound to say about human nature.’

Lisa Glass. For the rest of this review, click on: vulpes libris review

‘Vanessa and Virginia, as well as being both subtle and beautifully written, has lots of narrative drive. The descriptions of Vanessa’s paintings, the way they reflect and interact with her complex relationships, are particularly effective.’

Sarah Annes Brown, in Ariachne’s Broken Woof. For the rest of this review, click on Sarah Brown’s review of Vanessa and Virginia

‘Superb, really exceptional!’ Sally Cline, author of Zelda Fitzgerald.

‘beautifully written – vivid yet economical’ Deborah Arnander, translator

‘a very remarkable achievement – seamless play between two worlds, fact and fiction’

Andrew McNeillie, editor of Virginia Woolf’s diaries and essays.

‘rich and economic – packed with concentrated language

which I wanted to say out loud for the pleasure of it!’ Alesha Racine, poet.

‘incredibly evocative, particularly the childhood section’

Anna Snaith, author of Virginia Woolf.

‘it’s a book you read and re-read and read again for the sensual pleasure that carries you through as fast as the child [Virginia] skipping off to look up the virgin queen in her father’s library’

Angela Morgan Cutler, author of Auschwitz.

‘I was impressd by the beauty of the language, by the compression, by the way that the technique, like Cather’s “touch and pass on”, creates such a resonant text for readers even for readers who have themselves read a great deal of Woolf’.

Melba Cuddy-Keane, author of Virginia Woolf: The Intellectual and the Public Sphere.

‘boldly sustained in its central narrative device, not to mention the marvellous “painterly” detail’

Christine Crow, author of Miss X or the Wolf Woman.

Kettles Yard was the Cambridge home of Jim Ede, a man who put a great deal of thought into his surroundings. He was passionate about art and collected paintings and sculpture – his house is full of extraordinary works by such diverse artists as Pablo Picasso, Barbara Hepworth, the Cornish painter Alfred Wallis, and Ede’s grandchildren.

Kettles Yard was the Cambridge home of Jim Ede, a man who put a great deal of thought into his surroundings. He was passionate about art and collected paintings and sculpture – his house is full of extraordinary works by such diverse artists as Pablo Picasso, Barbara Hepworth, the Cornish painter Alfred Wallis, and Ede’s grandchildren.